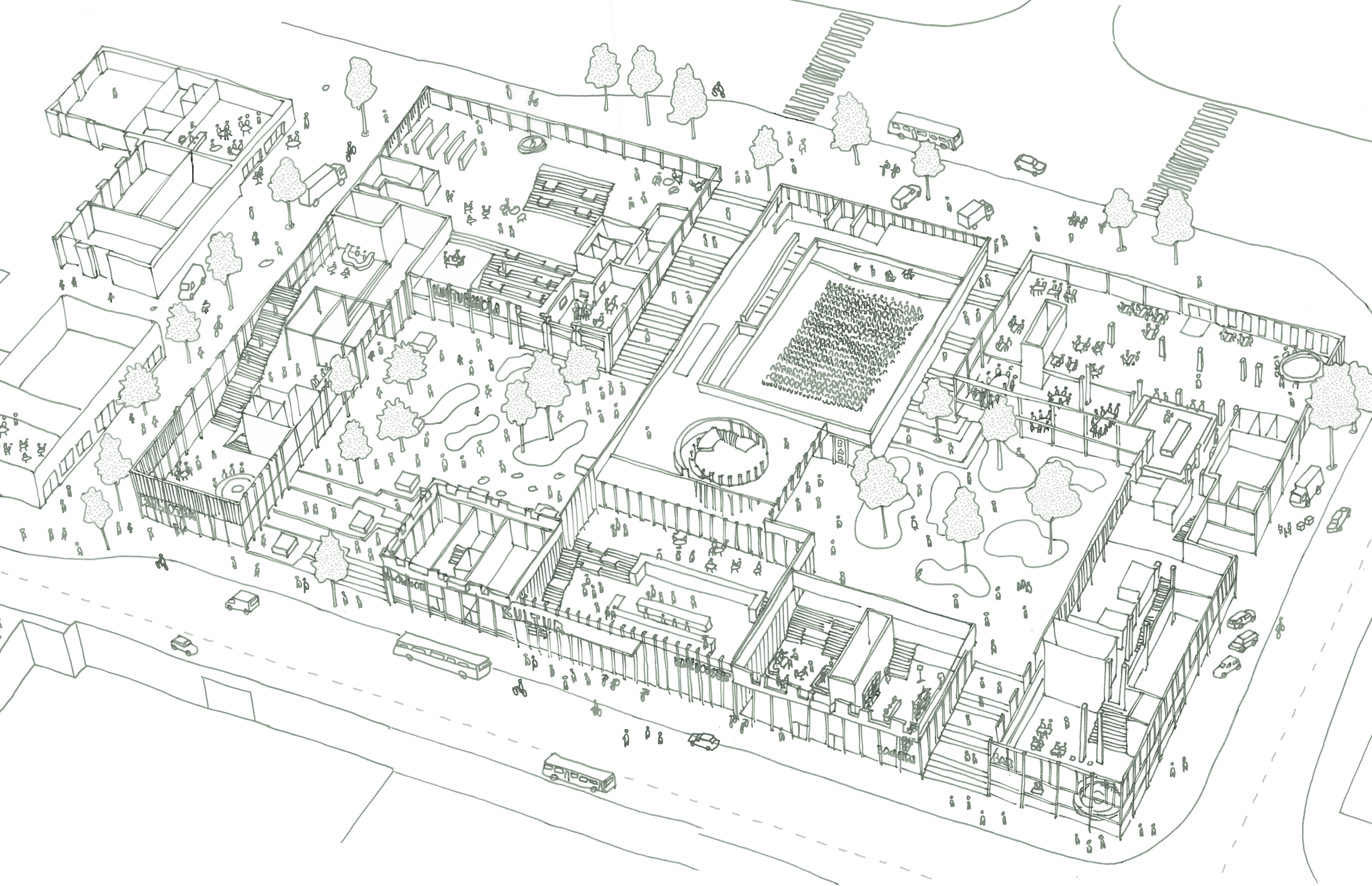

Project Name: Cultural Block Östersund

Location: Östersund, Sweden

Date Designed: 2017

Date Completed: In Progress

Size: 26,500 sqm

Client: Östersund Municipality

Programme: Public Space

ABOUT Kjellander Sjöberg

Kjellander Sjöberg is based in Stockholm, Sweden and provides architectural and urban design services in the Nordic countries. Established in 1998, it is currently a multi-nationality medium-sized office led by partners Ola Kjellander, Stefan Sjöberg, Mi Inkinen and Lena Viterstedt. Kjellander Sjöberg believes that the built environment influences social progress, quality of life and cultural richness. Innovation and sustainability are 2 key drivers in their design. Creating work that is innovative and unexpected while maintaining synergy between resources, high quality built environments and rich social experiences is a part of their philosophy.

ABOUT Cultural Block Östersund

Gustav III Square is historically known to be a public square and was used as a marketplace, entertainment, demonstrations, and meetings. As the city developed, Gustav III Square transformed into a bus terminal. Östersund municipality, together with a real estate company Diös, initiated research to transform the square into a public gathering point for the city with multiple programs. This is done through a consultation process that is reviewed by multiple stakeholders as well as the public.

Kjellander Sjöberg

Interview with SJOBERG Stefan of Kjellander Sjöberg

Insights and Takeaways

1. HOW HAS THE COVID SITUATION AFFECTED YOUR WORKFLOW?

Sweden has been both criticised for its covid stance, we have been having quite an open society still, people trust the government. We trust and act upon what they do. So we could use Teams and digital meetings and interactive sketches tools without meeting (in real life), and I think that works and this kind of digital processes benefitted us so much.

We really use a lot of sketching. Before Covid, I would say that it doesn’t really work to have these meaningful discussions and sketch on the product in real time, but now I think it is very possible. However, having said that, It is difficult to have very creative early design processes if we don’t meet. We have smaller teams of about 3 to 4 ppl coming in to meet and develop products. In the later phases it is more streamlined where you know your tasks for the coming weeks and focus on the part of the building, and you can have a dialogue online.

Creative processes are still working. We are working on this London project in Enfield, where we created a team in Stockholm and there are like two more design teams in London for landscape and buildings, infrastructure and all that. So I think that works really well, and we can still be creative with new tools. But to a certain degree, we are old fashioned I would say. We like to do hand sketching and models parallel to digital tools. It is really nice to be able to do that. We are a big studio of usually 40 people, now it’s around 5-10 people. So I think it works in a sense that Sweden is still open and we can still meet in a smaller group.

2. DO YOU HAVE ANY SPECIFIC BOOK THAT YOU WOULD RECOMMEND STUDENTS TO READ?

Oh, I’m such an illiterate architect. I read a lot, but not always about architecture anymore. That’s a difficult question. Now, I tend to read the same authors. Recently, I read a lot of Virginia Woolf and I read some Murakami books, like serious reading, and then I switched to another author.

I think a book that we have read in the office for a master planning project has been Soft City by David Sim from Gehl Architects. So that’s the most, I would say the most recent book I read that has influenced the way we think about planning. The Soft City about this kind of feeling that the city must be adaptive: both the built structures and the open space structures. Also the soft things like people and parks and public spaces are as important as the buildings. It is a really good book. They go through the Gehl approach in focusing on walkability, and a bicycle culture in a good way in that book.

3. WHAT ADVICE WOULD YOU GIVE TO ARCHITECTURAL STUDENTS?

It is difficult, but it is a very nice profession. I have been doing this and having my company for over 20 years now. I go to work everyday and I really think it is fantastic, it is a fantastic occupation. You get to integrate with so many people and the society at so many levels, as an architecture student you should really reflect on what you want to get out of architecture. Do you do this for other people or do you do this for beautiful graphics or great constructions, or how to push how to build things not to harm the planet? It is good to ask yourself these questions. It is evolving, you do iterations of these in a good project, as an architect you realise there are all these iterations over the years, you constantly feel that you don’t know enough, don’t have enough technical skills. I encourage people to get as rich of a training or work experience as you can, and keep doing things because it is fun, and do more projects with the community. In Sweden we have these projects called summer houses: simple buildings for anyone. You can work on these small projects to train and maybe reflect on what you want. You can also head to large architecture offices and work for a while as a student, and maybe sometimes you feel quite small, and you can’t really affect the direction of the project or the office, but I still think that asking questions and doing things with other people in teams is great.

Interview Transcript

Q1: Kjellander Sjoberg (Schellander Sjoberg) has a vision to improve living conditions and environments when designing and contributing to neighborhoods and meeting places. How are the local community and local stakeholders involved in the design process?

There is a difference between the urban design and planning projects and architectural projects. We do both figure planning commissions and we work with a lot of architectural projects like residential development. In the first one, when we look at the bigger urban projects, we sometimes have to take the perspective of doing something really good and long term for the community. We certainly do enjoy doing it with the community, and the ambition is to have good dialogue and really meet different local groups and initiatives. However, that doesn’t always happen, of course. We work with different municipalities and sometimes even private companies or clients that would own a big piece of land. Our ambition is to find these local communities and work with them. There are different ways you can go about this. We can find more representative groups or people, or if you just trust that the key people that would really use the place will join. We think that it is really important to have a kind of framework, an overall framework that would make this development sustainable. And people can add to that, maybe change it a bit but somehow add to it. If there is an initial framework in place it is easy for people to add their input to it.

Q2: Referencing the recent public hearing for the Gustav III Square, held over two months, how active was the community in actually providing feedback and how useful were they?

(*Prompts: E.g. Substantial amount of respondents vs a handful of people giving lots of their own personal views. How much of this feedback is actually being incorporated.)

There had been different dialogues in the city of Ostersund in northern Sweden. The dialogue is about what kind of programming or what kind of brief that we would have. As an architectural company we work together with private developer Diös who will actually build the buildings. I think the municipal meeting (public hearing) is perhaps a bit late (for this project). A lot of times, the people are worried that the public voice will change the product too much. However, I think in this case, the ambition is to build a new hotel and new residential units and commercial units, like shops and restaurants facing the streets. But it is also a really clear program with public spaces that are informal built on the code of that city, which is a really informal older wood timber city with narrow alleys.

I think the public hearing is really important and the public hearing that took place in this case is kind of legistated: the kind of procedure that you need to follow as a city in Sweden when you plan for a site. In some cases, it works: a lot of actors and a lot of stakeholders get to be heard automatically. That is the base of planning in Sweden, at least, or in many of the northern Scandanavian countries. Outside of that we would like to have this co-working process with municipalities or groups.

To answer the question quickly, there was a public hearing and people could sign and hand in their complaints or even suggestions. And that works at a general level, but it would have been so much more satisfying if the dialogue went through the process as it continues.

The basic model here is quite democratic, we have it in our DNA but then it could be really nice to really sit down and talk to people. Most people probably don’t know how exactly to shape this kind of square and public development, but still you could still get some public ideas and public feedback on how they would like to use it.

Q3: For projects like this in Sweden where you are working with municipal agencies, how much influence does the developer (e.g. Diös pronounced Dee ers with silent r) have over the decisions of the design process as well as incorporation of feedback?

In Sweden, like everywhere else, architects don’t really have the power to fully decide, since there are goals like financial goals. But I think it’s how you frame what kind of question you raise, about the way we as architects or planners frame projects and raise questions that really shapes what will be done and built. I think raising a dialogue is important and I think in this case in Ostersund you mentioned that there was a lot of discussion about how the public character of the project could be truly public, because if you privatise (in this case roughly about 70% of the project), it is a square but it is a bus square right now, how should we go about designing it? By raising questions like what kind of quality space, studying and walking around to find a meaningful way to shape these urban spaces, in that case you might find a strong concept that allows you to satisfy the municipal’s and developer’s needs while shaping the direction of the project.

Q4: In Singapore, the recent coronavirus situation has shed light on a demographic largely neglected in the process of design for community spaces, which are the migrant workers. Drawing parallels to Sweden, the country is known to have taken in a large amount of refugees over the years; one of the highest intakes in the world over the past decade. Though minor compared to the population, this steadily growing new demographic presents a new question about the integration of refugees into the discussion and design process of community spaces. What are your takes about how this process would work in Sweden? Perhaps from there we could extract relevant points for application in Singapore.

I think it is a really huge question that we could discuss for a couple of days (laughs). I would say since the refugee crisis in 2015, we received many migrants that fled from mainly Syria. This of course affected the population and the way we as the planning profession acted in Sweden, we are mostly active in Stockholm and Malmö, but they present similar challenges. In Malmö there is a huge focus on inclusion and trying to make the city, both the fabric and other aspects like the population and education more connected and integrated. The positive side in Sweden, is that the planning process has democratic pivot points that aims to provide everyone with the same proximity to care, free education, that’s including everyone whether you are a citizen or migrant. You have these benefits and opportunities. But then again in the physical reality, you have neighborhoods that are deprived, they tend to be clusters of people new to Sweden. The positive thing is that we try to shape an equal society, but I don’t think we are there yet because we still have much to catch up on since 2015. I think there is a strong feeling that everybody must have a home to live in, a kind of basic need. The needs we are not achieving yet is really including everyone in the Swedish society. I think everyone is welcomed in a way, but we don’t really have the financial and political strategies to curb this problem.

We did an exhibition recently called Commoning Kits in Malmö at the former design centre, and we had this idea to work with 15 architecture firms to create kits to kickstart the community. If there is a community perhaps it can be strengthened by empowering the community there to work together like an open market, a centre or dance floor; which is a place to dance outside with a roof. If we do projects for non-profit like in Africa, to build schools, there’s a lot of projects like that that are also needed in Sweden, and opportunities to do temporary things in Sweden. We feel like we need to be bottom-up when we plan, and one way would be just to let communities use leftover space so you use it temporarily, this is something we pushed quite a lot. I would say we don’t have the answer or key to how to do this in Sweden, but when we work in urban planning, it’s really about how to connect all the neighborhoods more so they are not isolated. It’s through infrastructure, streets, devices like schools and community centres with social spaces to meet and discuss. I don’t know over at your place, but over here Black lives matter was a big thing, which was terrible, but it was needed (a sad side of the story), but it went well in the sense that the police force and the political level met with the demonstrators and had a dialogue. But the sad thing was that a protest was still needed even though Sweden is thought to have reached so far, but I think the positive side is that we try.

Q5: As an architect, you always have an aim at the start of the project on how your design contributes to the context, the city, and the community that uses it. There is a rigorous design process to achieve this aim, from understanding the programme and users to developing a design concept and assessment of details. For both completed and ongoing projects, how do you assess the level of success of achieving these goals? What makes a project more (or less) successful to you?

Usually a successful concept is one where you can satisfy the cities’ municipal needs and satisfy the client’s commercial needs. In the best of worlds that’s not really the conflict, because you want a space like this to be popular and used, and the retail, restaurants and hotels to be popular as well. So I think the key is coming up with arguments and strategies that are beneficial to as many parties as possible. If the scope is too narrow here in Sweden, a lot of projects stop in the planning process, sometimes due to financial difficulties, but also because nobody really wants to go ahead with the planning and design. In general, of course, we never decide anything as architects, but if we are having a successful day, we can still frame the projects so it really is about the interests we like; sustainable developments and a better place for people and the planet. There’s always a struggle and work needed to get there. We as architects always try to do very sustainable projects, and it is very hard to hit all these targets but hopefully you get to steer the project’s position to a positive direction although you did not hit all your targets of sustainability, livability or inclusion etc.