Project Name: Nepal Rebuilt House

Location: Katunje, Dahding Besi, Nepal

Date Designed: 2016

Date Completed: In Progress

Size: 60 sqm

Client: Future Village Foundation & IDEA Foundation

Programme: Residential

ABOUT Atelier-3

Atelier-3 & Design For People Co. has been a leading force in developing and promoting sustainable lightweight steel houses in rural & ethnic areas since 1999.

The main goal of the practice is to improve the infrastructure and living environment of the rural area, leading to sustainable development as well as an ecological society.

The team believes that everybody has the right to adequate and affordable housing, unfortunately, the current housing situation is urgent, vast and unsustainable (both economically and environmentally). It has been their mission for the past 15 years to design and develop innovative solutions to these problems. The team does this by designing from the ground up and has developed simple and compatible construction methods that result in housing delivery that is fast, saleable, cheaper to erect, and better for the environment than current building systems.

ABOUT Nepal Rebuilt House

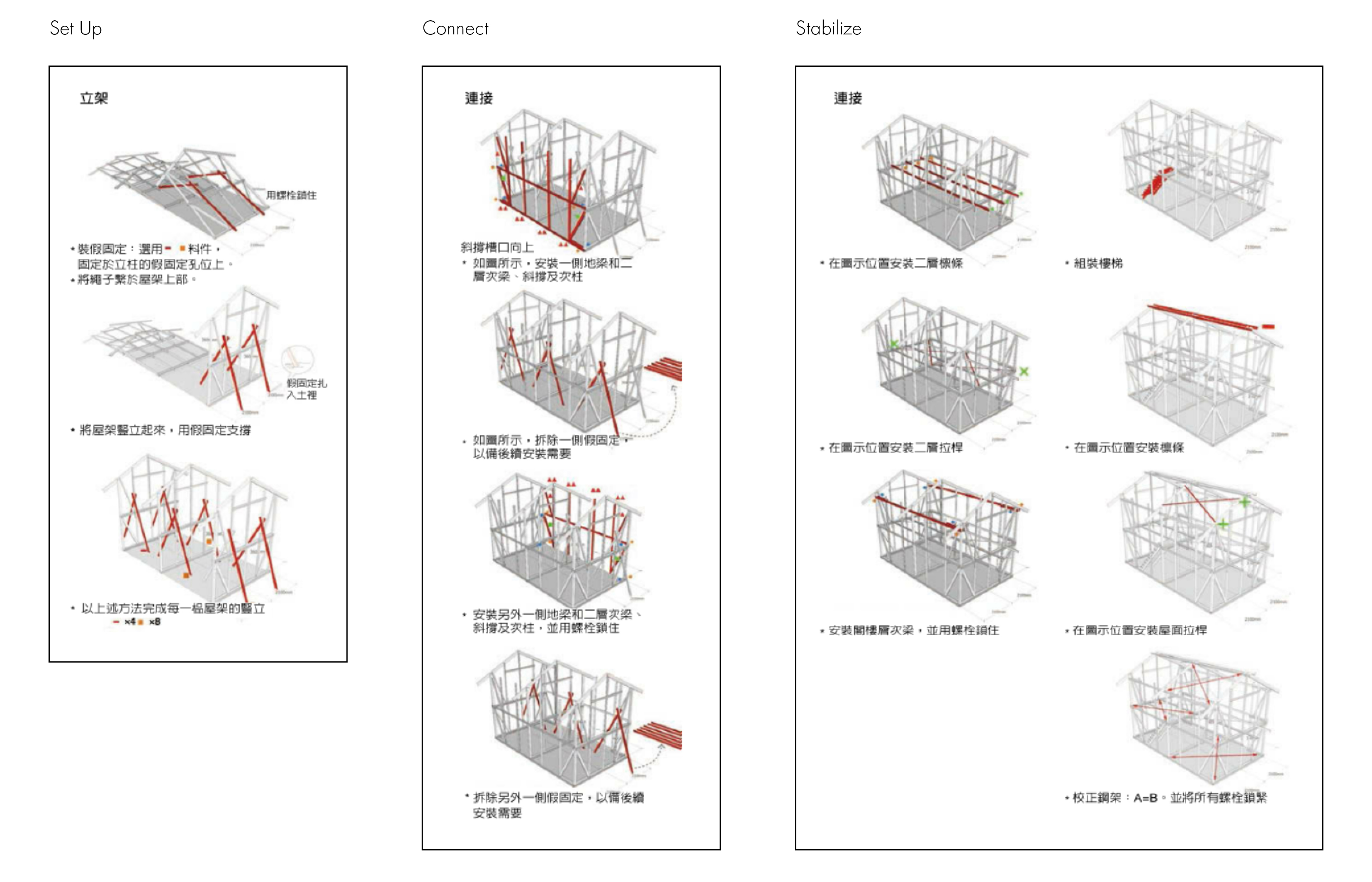

Nepal Rebuilt House is a total 60sqm double storey house design by the team that only required simple building techniques to construct. The project aims to rebuild the village by working together with the locals and making use of the existing construction methods and materials on site.

Nepal Rebuilt House

Interview with HSIEH Ying-Chun of Atelier-3

Insights and Takeaways

1. MOST OF THE ARCHITECTURE PRACTICE NOWADAYS IS DONE VIA THE INTERNET DUE TO COVID. HOW CAN ARCHITECTS REMAIN CONNECTED TO THE PEOPLE THEY SERVED GIVEN THE TREND NOW? HOW COVID-19 PANDEMIC AFFECT YOUR WORK NOW AND IN FUTURE?

The online communication mentioned here is only the exchange and communication of information. The real immediate impact of the COVID-19 is the logistics and the flow of people. There is no problem with the flow of materials, but there will be problems with the flow of people, and this is the most suitable place and time for our system. When people cannot move, local materials and manpower must be used to build a house. This is the original intent of our system. It can simplify the structure and does not require special skills, and it can be completed in a closed community. The logistics only has steel structure, the transportation cost is low, and the cost of building the house is relatively low, and the remaining materials are local materials. Therefore, under this trend, our system can be more connected with the public.

2. WHAT IS THE TITLE OF A BOOK YOU RECENTLY READ? WHAT IS YOUR FAVOURITE BOOK? WHAT READINGS WOULD YOU RECOMMEND TO ARCHITECTURE STUDENTS?

One of my most recent books is “Architecture as Metaphor” by Kojin Karatani. One of my favorite books is the Tao Te Ching, written by Lao Tzu. It is also recommended to students in the Department of Architecture. The ideal society described in the penultimate chapter of the Tao Te Ching is similar to “visible region from eyesight” in Plato’s Utopia. The best state of an ideal society is the state of bliss of “ruling by doing nothing”, without much “doing” by the rulers. In modern countries, the smaller the better, just like Singapore!

3. WHAT CAREER ADVICE WILL YOU GIVE TO THE YOUNGER ARCHITECT WHO IS PURSUING IN THE FIELD OF HUMANITARIAN AND SOCIAL ARCHITECTURE?

We are concerned about the problem of 70% of human settlements, which is a huge area that most professionals have not been able to touch on in the past. Therefore, no matter how many professionals or non-professionals, if you want to dive into this field, there is always work, hence, don’t worry about any work problems. As long as you are open-minded, you can always see things that need to be done.

Interview Transcript

Q1: In most of your projects, be it post-disaster or not, what is the role of the government or local community in this architecture process you described? How are their roles differ in both scenarios?

Most people do not understand and have no time to understand our work in the disaster area. Because our approach is non-mainstream, we need considerable experience and foundation to be able to execute it. Not to mention that the government or the general public cannot understand it. People in the field of architecture may not be able to understand and agree with it. Even if there are conceptual ideas, it will be challenging to execute as well.

First of all, the building we emphasize is production behavior and participatory rather than consumer behavior. Especially in post-disaster reconstruction, the matter of allowing residents to participate is beyond the general mainstream idea. We didn’t know until we entered the disaster area that 70% of human housing has nothing to do with what we generally call the construction profession. What the existing construction system in the market can do is not aimed at the 70% of human beings. That field is blank.

The so-called 70% of human settlements, regardless of post-disaster or non-disaster, the problems encountered are the same, but the problems of housing in the disaster area must be solved in a short time, which makes it more compressed. Most of the houses of mankind are built by residents, but there is no such thing in our knowledge and education system.

Q2: When you begin a new project in the village, especially in a foreign country, how do you build trust with the locals, especially when it is a post-disaster project?

What we generally call “communication” is actually very difficult, especially when it comes to architectural behavior. It contains many complex values, such as aesthetics, habits, emotions, social interactions, communities, etc., so communication is very difficult, whether in the tribe or overseas. For example, Christopher Alexander tried to solve this problem in “Pattern Language”, and Kojin Karatani’s “Architecture as Metaphor”, many of which talk about language, expression, and metaphorーAnd the behavior of these buildings we see actually has various meanings behind it.

For example, when we first came to this Thao tribal community (Ida Thao; reconstruction in the 921 earthquake in 1999), how did we communicate with the residents? Basically there was no communication. On the surface, user participation did not happen because they couldn’t understand your drawing, they couldn’t understand your language. Because we were strangers, it was not easy for them to express themselves. So no matter where the project is, do not communicate. The only effective communication is through “behavior” and “action”. Hence, we tried to build a room as our workstation at the gate of the tribal community initially. The residents of the tribe would come over when it was built and give comments, such as how the bamboo should be cut and unknowingly they participated in the process.

The configuration of the Thao family house is arranged according to the division of labor by the clans. Some are responsible for hunting sacrifices, some are responsible for sowing sacrifices and etc. The festivals are held by different families in turn. In the past, everyone held these ceremonies on the drying valley, but now there is no drying valley, so the square in front of the house is configured as a ceremony space. But for these rituals and other life habits, most of the tribe would not share the details to outsiders. Therefore, in the process of building houses, we continue to demolish and reconstruct to achieve the current state.

What is the metaphor of architecture? It is actually a specific value behind the architecture given by the designer rather than naturally generated. A building has to include this value, even in its spirit, symbol, form, etc. It is created by the architect (Making), but in the end it may be hidden inside the architecture and may not be seen, because the process of generation (Becoming) is very complicated, and the generated outcome may not be the main part. Thus, the so-called communication is not the communication that most people imagine, and that communication is the most difficult.

Q3: How did you overcome constraints or conflicts involving the locals in the building process?

We know that conflicts always arise inevitably just like one happened in your rebuilt project after the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake (杨柳村). The “guerrilla building” method (游击造屋) was adopted too, unpredictably, the villagers ended up having conflicts due to differences in the use of materials and construction methods, resulting in the inability to collect all the material costs paid in advance by the team. How do you resolve the conflict at that point in time or what do you think could be done better to prevent this kind of event to happen?

In fact, we have never had any way to reduce or avoid conflicts. As mentioned earlier, architectural behavior is extremely complicated. The situation in the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake in Yangliu Village is not uncommon even in the next few projects. Until now, our only practice is to collect payment before delivering.

Q4: You described the city construction model as consumer behavior and the rural area’s construction model as production. I wonder if the rural area’s construction model can be applied in the cities. On what form do you think will it take if it is to implement this in city area and does it limit by the scale of the project?

Of course, we have proposed ways to carry out such behavior at high-density living in an urban environment.

The concept of “Supports & Infill” has been put forward by various people, from Bauhaus to John Habraken’s “Open Building”. This concept was explicitly put forward in our projects such as Youth Housing in Shenzhen and Hualien, Taiwan. The main structure of buildings should be like bridges and roads – they are public facilities. Once the man-made three-dimensional platform is created, the space inside should be left to the residents and citizens to fill in themselves.

Is housing in the city a consumer behavior or a production behavior? In cities, the interior decoration of houses is constantly being demolished and rebuilt, while the illegal roofs are all built by people themselves. These are all production activities. Then why did we not consider these changes when we designed the houses in the city? The predecessors in the history of architecture have taught us that the supporting body and the filling content must be separated, and the piping can be assembled and disassembled, but we have not made enough preparations for this.

How can production behavior not be in the city? It definitely can be. The concept of a people’s city is that the government or developers lead the construction and maintenance of the main public infrastructure, while the space rights within the framework are sold to the citizens, allowing them to adjust themselves. This concept is closely related to the communication between the communities and the interaction among the residents in the city, similar to the countryside, where every household owns a courtyard, such that building a house is definitely not a simple individual behavior - it has something to do with the neighbors.

Q5: Most of your projects focused on the rural village and that your architecture can be seen as resistance to some of the government policy such as the one Bunong village (布农族村落) where some of the villagers resist in moving from their village. What is your view on urban villages (slums) such as one in Indonesia, India or Philippines where people living in these “illegal” squatters faced the fear of being eviction every day and yet they have already been living in this place for years or some decade? How can architecture be used as a form of resistance and validate their existence in the area?

Building a house together is a form of ‘Empowerment’. In the reconstruction for the Thao community, building a house together reconciles the residents and forms a united force to negotiate with the government. A long period of compromise and communication finally led to a consensus. In the tribe, the so-called democracy is compromise. The value of democracy is not that “the minority obeys the majority” but that “the majority respects the minority”, that is, compromise. From African tribes to Taiwan aboriginal chambers, British parliaments, etc…. Meetings are all held in extremely small spaces. With everyone crowded in an unbearable small space with limited mobility, when minority resists, majority will tend to reach a consensus quickly through compromise. Hence, compromise is the core value of democracy.

Most of the problems in all slums are about the land. For example, in Haiti, most of the land ownership is controlled by six families, so there is no way to rebuild after the earthquake. In this state, there are several reasons to adopt our method. First, our structure can be easily disassembled and can be regarded as not permanent. Under this situation, it will not cause a significant threat to the landowner, and it will be easier to accept. Second, for slum residents, building houses as a production behavior is completely acceptable because originally they have been building the houses and assembling it by themselves and they can do it even more smoothly and take into account the structural safety. All slums are production behaviors, and it aligned with our system perfectly.

There are very complicated interpersonal relationships in the slums, which cannot be solved by any current technologies or means. All collaborations must be resolved by the locals themselves, and no one can intervene if it is built by an inch or less. In this kind of community, the subjectivity of each resident is very strong. In fact, it is the same in the tribe, we cannot intervene directly and we must observe their words and actions from the sidelines.

Q6: What is your biggest take away in your works with the locals?

The biggest gain is that it is fortunate to be able to re-understand the so-called “tribal civilization” in modern days. Tribes are likely to be an introduction to a new civilization in the future.